Gabriel’s Rebellion and James Monroe by Wilson LeCount

Gabriel was born into enslavement on Thomas Prosser’s tobacco plantation in Henrico County, Virginia in 1776, amid revolution. Little is known about his early life, but by all accounts he was well respected amongst the enslaved population, and he was also literate, a skill that would later become illegal to teach to any person of color in Virginia after 1831. He and his bother Solomon were skilled craftsmen who worked as blacksmiths; Gabriel also worked in the Richmond foundry, where he had valuable interactions with laborers of diverse backgrounds – free and enslaved, White, and Black.

The enslaved population of Virginia were Inspired by revolutionary movements they had seen succeed in their lifetimes. The American Revolutionary War (1775-1783) left many enslaved persons feeling cheated and confused, as the ideals of liberty and independence were not universally applied to people of color at war’s end. Virginia, home to many of the great American revolutionaries, had by far the largest enslaved population of any state at the end of the Revolution with almost 300,000 enslaved individuals by 1790.[i]

[https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:An_Overseer_Doing_his_Duty_1798_-_Benjamin_Henry_Latrobe.jpg]

Across the Atlantic, the French Revolution of 1789-1799 saw the downfall of an unjust power, but also what many Americans thought to be a threat of unrestricted democracy. The Haitian Revolution was a powerful influence on the enslaved and enslavers in the U.S., ramping up both hope and fear for these groups respectively as they saw a successful revolutionary movement by people of color against the institution of slavery in the North American hemisphere. These influences, mixed with years of unjust treatment and exploitation, led Gabriel and others to conspire to conduct their own revolution in Virginia. Throughout the late summer of 1800 Gabriel and his brothers started plotting. They made contact with enslaved and free People of Color over a large area encompassing 10 counties and the cities of Richmond, Petersburg, and Norfolk. With no significant body of US Army troops in the region, White Virginians had only local militia units available to oppose an attack on the large scale Gabriel envisioned.[ii]

Organizing Gabriel’s revolutionaries happened mostly through word of mouth, spread by trusted officers in Gabriel’s cohort, but there were also rumors of Frenchmen aiding in the organization of the rebellion as well. The exact number of people organized is unknown, but Gabriel planned to liberate enslaved people in Henrico and the surrounding counties with the goal of capturing Richmond, its armories, and key leaders in Virginia (including Governor James Monroe) to force an end to slavery. Mostly enslaved men were recruited for the attack against Richmond, while those sympathetic to the cause, such as Quakers, Methodists, Frenchmen, and potentially poor whites would be spared from the bloodshed. Gabriel and his brother Solomon made a handful of swords out of scythe blades, turning the tools of oppression into the tools of liberation, as well as musket balls for when muskets would be captured.

Rumors of revolts lingered in this region as armed volunteers were called up to protect the city of Petersburg earlier in August of 1800 from a suspected attack.[iii] All was ready to go for Gabriel; However, on the night of August 30th, the planned date for the revolt, a severe storm swept across Henrico and Richmond, forcing Gabriel to call off the plot. Gabriel was then betrayed by two of his followers who were anxious of repercussions and were promised their freedom in exchange for information, and Monroe was alerted immediately on August 30th. Monroe called up the Militia on September 3rd to “use every exertion to apprehend all Slaves, servants, or other disorderly persons unlawfully assembled, or strolling from one place to another without due authority and have them dealt with as the law directs.”[iv] Gabriel escaped toward Norfolk but was captured and brought to Richmond where he stood in front of a trial of five judges, not a jury.

During the trials, references of the Revolution were brought up many times, with one defendant supposedly claiming,

I have nothing more to offer than what General Washington would have had to offer, had he been taken by the British and put to trial.

Gabriel’s Conspiracy, “Death or Liberty,” Library of Virginia https://www.lva.virginia.gov/exhibits/deathliberty/gabriel/index.htm

Such a defense might have struck a chord in a country that so recently fought a war for independence, had the accused not been Black. Despite this, 26 people, including Gabriel, were executed as conspirators, eight more were sold away from the Richmond area, 13 were pardoned by Governor Monroe, and 25 were acquitted.

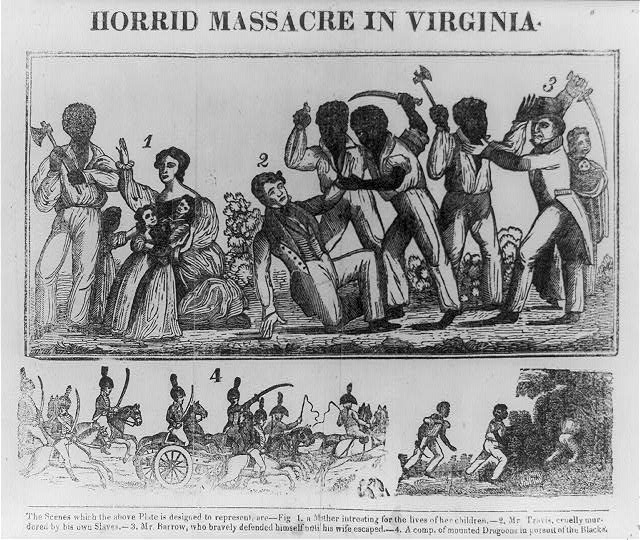

The hanging of Gabriel did not put an end to the story; another conspiracy was thwarted in 1802 by one of Gabriel’s followers named Sancho. The memory of both attempted uprisings would burn deeply into the minds of enslavers and the enslaved alike for decades. Enslaved people continued efforts to liberate themselves throughout the 19th century, including the attempt of Nat Turner, who put many of Gabriel’s plans into action with his revolt in 1831. Fears of these uprisings led to further restrictions on enslaved people throughout the South, increased legislation protecting the institution of slavery, and further tension between free states and slave states as they battled with questions of national and regional ideals.

The issue of punishment weighed heavily on James Monroe, as he battled with the hypocrisy of executing those who were rising against what they knew to be an unjust power, just as he had done so fervently during the Revolution. He struggled with maintaining dominance, having mercy, and how his actions would be viewed on the world stage. The effect of Gabriel’s conspiracy would also help to influence Monroe’s support of the American Colonization Society later in his political career.

If you would like to learn more, click here for a video by the James Monroe Museum.

[i] David Fienberg, Slavery in Virginia: A Selected Bibliography (Richmond: The Library of Virginia, 2007).

[ii] In Solomon’s testimony, he is quoted “The reason why the insurrection was to be made at this particular time was, the discharge of the number of soldiers one or two months ago – which induced Gabriel to believe the plan would be more easily executed.” (Philip J. Schwarz, Gabriel’s Conspiracy: A Documentary History (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2012) Pg. 37). Tensions between the U.S. and France led to the recruitment of additional army regiments in the late 1790’s, one of which being stationed near Richmond in 1799. This regiment was disbanded in June of 1800 to the pleasure of Monroe and other Southern Republicans who feared the economic and political implications of a large standing army.

[iii] James McClurg to Monroe, August 10th, 1800. In The Papers of James Monroe; Vol. 4 pg. 391.

[iv] Monroe to the Commandants of Militia Regiments. September 3rd, 1800. In The Papers of James Monroe; Vol. 4 pgs. 400-401.

You must be logged in to post a comment.