by Scott Harris, Executive Director, University of Mary Washington Museums

Scott,

I’ve never seen this image . . . Is this even Fredericksburg? Best,

Michael Spencer, Associate Professor Department of Historic Preservation University of Mary Washington

The brief message above from my UMW colleague Michael Spencer showed up in my email inbox at 1:22 PM on Tuesday, January 10, 2023, accompanied by a link to this photograph:

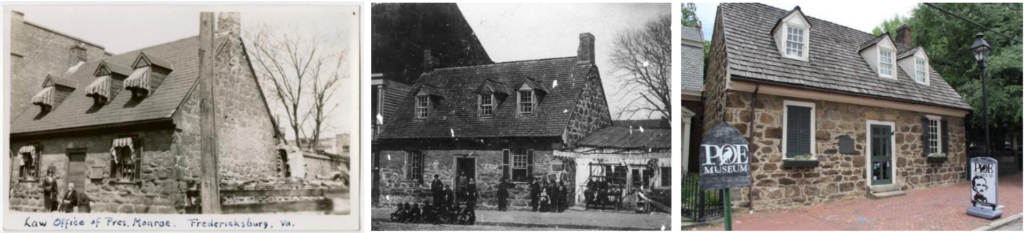

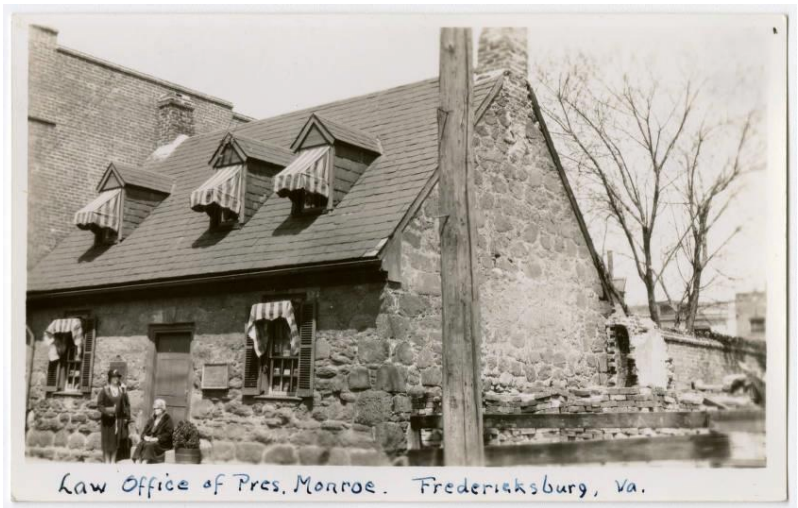

Not surprisingly, the handwritten caption caught my attention immediately, as it had Michael’s. There was no ambiguity about the citation: “Law Office of Pres. Monroe. Fredericksburg, Va.” The only problem? It wasn’t Monroe’s law office. Before going any farther, some background is in order.

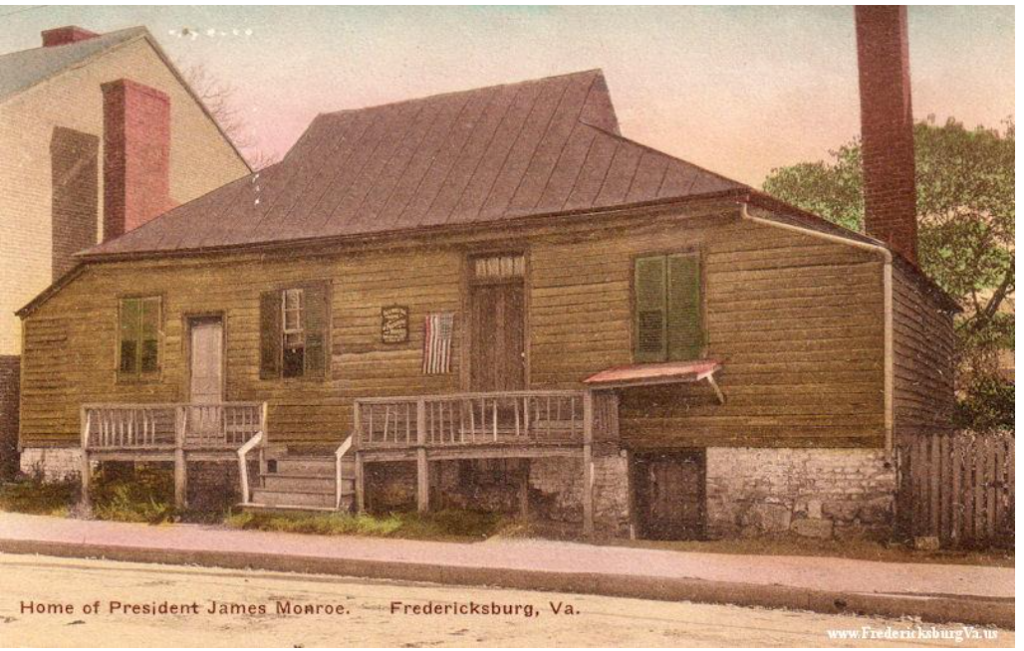

Misidentification of homes and other buildings associated with James Monroe has practically been a cottage industry (pardon the pun) for well over a century. Histories of Fredericksburg published in 1908 and 1922 describe a frame house that was advertised as the “Home of James Monroe,” located on Princess Anne Street (see image at right), but the attribution is not supported by clear documentation. [We’ll explore the efforts to research this property in a future newsletter article.]

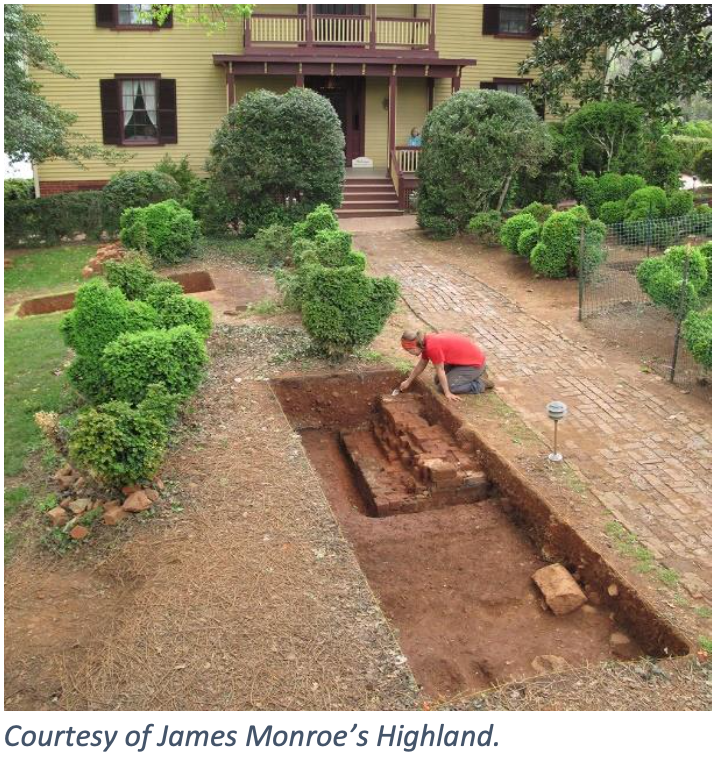

Our colleagues at James Monroe’s Highland in Albemarle County, Virginia (formerly known as Ash Lawn-Highland), have also contended with misinformed traditions about the nature of their property. Monroe owned the 1,000-acre farm from 1793 to 1825. For many years, a small portion of the structure (which was altered by the addition of a large, two-story house by later owners in the 1870s) was thought to be the dwelling for the Monroe family.

Dendrochronology (tree-ring dating) undertaken in 2015 proved that the small building was a guest house built with lumber from trees harvested between 1815 and 1818. Archaeological digs discovered the foundations of a much larger home, consistent with Monroe’s descriptions of the family’s residence.1

And what of the intriguing picture sent by Professor Michael Spencer? I shared the image with other James Monroe Museum staff members, and we quickly determined that it was not a view of the Monroe law office (which, as noted, is traditionally regarded as being at the museum’s 908 Charles Street location, though not in the brick buildings that post-date Monroe’s ownership). The structure in Dr. Spencer’s shared photo is of stone, not brick, and does not align with features of the Charles Street property. So, where/what was it?

Some quick Internet searching soon provided the answer. The building is the Poe Museum in Richmond, Virginia, as a comparison of pictures shows:

Having established the identity and location of the “mystery” building, the next question was, “Why was it labeled as the Monroe law office?” A little more research at the source website provided an answer, of sorts.

The picture is part of the Floyd and Marion Rinhart Photograph Collection at the University of Miami Libraries, accessible online at this link. It was taken by Jesse Sumner Wooley (1867-1943), a New York photographer who traveled to Florida regularly, often by automobile. His route took him through Fredericksburg on U.S. Highway 1, and his traveling party stopped in the city around 1928. In addition to the “law office,” Wooley photographed the Mary Washington House and the Fredericksburg National Cemetery (see all three photos at this link).2 The large digital collection of his photos documents many other visits to attractions in Florida, Georgia, Pennsylvania, and other states.

While Richmond isn’t identified as one of Wooley’s stops, he apparently did visit the Poe Museum, which was founded in 1906 and was thus already an established landmark in the city by the 1920s. Whether Wooley himself or someone else mislabeled the photo, it set the stage for a brief but interesting mystery to be solved by Michael Spencer and the James Monroe Museum staff nearly 100 years later.3

Notes

1 For a discussion of Highland’s evolution, visit https://highland.org/discover-highland/.

2 Jesse Sumner Wooley biography at the University of Miami’s Richter Library website. Wooley’s three photographs, two of which

are of actual Fredericksburg sites, are part of the University’s online Floyd and Marion Rinhart Photograph Collection. 3 https://poemuseum.org/about-the-poe-museum/.

You must be logged in to post a comment.